Z80 MasterClass: Finite State Machines

Hi there! If you're into Z80, finite state machines, or CP/M, you've come to the right place. In this example of a not-so-simple Z80 finite state machine, we're showcasing the implementation of an CP/M path parser.

In this demonstration, we'll be parsing a CP/M path that includes the drive, the user area, the name, and its extension. As an example, consider 2A:TEST.DAT.

While using an FSM for this particular task may not be the most efficient approach, our goal is to demonstrate the technique. After that, you can apply it to more complex projects, such as the standard C printf function or a tokenizer for a programming language.

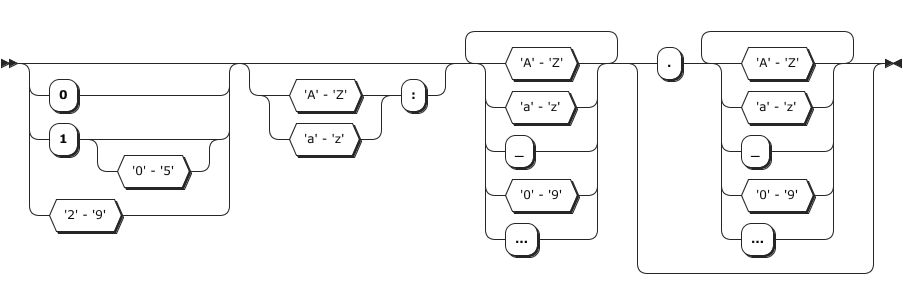

The CP/M Path Syntax and Semantics

Here's the syntax diagram for our parser.

There are two additional semantic rules that a valid path must follow:

-

Both the name and extension must be 7-bit ASCII strings and can't include any of the following characters: < > . , ; : = ? * [ ] % | ( ) / .

-

The maximum length allowed for the name is 8 characters, and for the extension, it's 3 characters.

Introducing the Finite-State Machine

We're tackle the parsing task using a Mealy machine. Our input will be the current state and a character, and our output will be a call to a function that handles that character, and the next state.

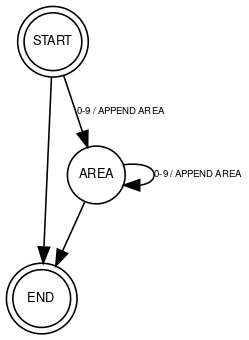

Let's create a partial FSM for parsing the area at the beginning of the path:

To encode this FSM we could create an adjacent matrix for state transitions, but that would consume a lot of memory. Instead, let's create a simple table of transitions. Each transition will be a row of data: <start state>, <condition>, <function to call>, <next state>.

We can describe our partial FSM like this:

START, 0-9, APPEND AREA, AREA

START, , , END

AREA, 0-9, APPEND AREA, AREA

AREA, , , END

The first row tells us that if we are in the START state and the next character falls within the range of 0 to 9, we will execute the APPEND AREA function and then transition to the AREA state.

The second row is a little different as it has no test or function defined. For this case, we've established that a missing condition always evaluates to true and a missing function means no code will be executed. Last but not least: the finite-state machine will follow the rules in the order they are specified.

Encoding the Finite-State Machine

We can tweak the way we encode our finite-state machine, depending on the number of states, conditions, and functions. Take this partial FSM for example.

It's got three states: START, AREA, and END. And all it takes to represent them is just 2 bits.

| state | bits |

|---|---|

| START | 00 |

| AREA | 01 |

| END | 10 |

The two conditions: 0-9, and the empty condition only require 1 bit.

| cond | bit |

|---|---|

| empty | 0 |

| 0-9 | 1 |

And the two functions: the APPEND AREA, and an empty function, also require 1 bit.

| function | bit |

|---|---|

| empty | 0 |

| APPEND AREA | 1 |

Hence, each full transition's description takes up 6 bits, with 2 bits representing the initial state, 1 bit for the condition, another 1 bit for the function, and the final 2 bits indicating the state to transition to. All in all, the whole FSM utilizes 24 bits, which is equivalent to 3 bytes. It's a compact representation, good enough for the job.

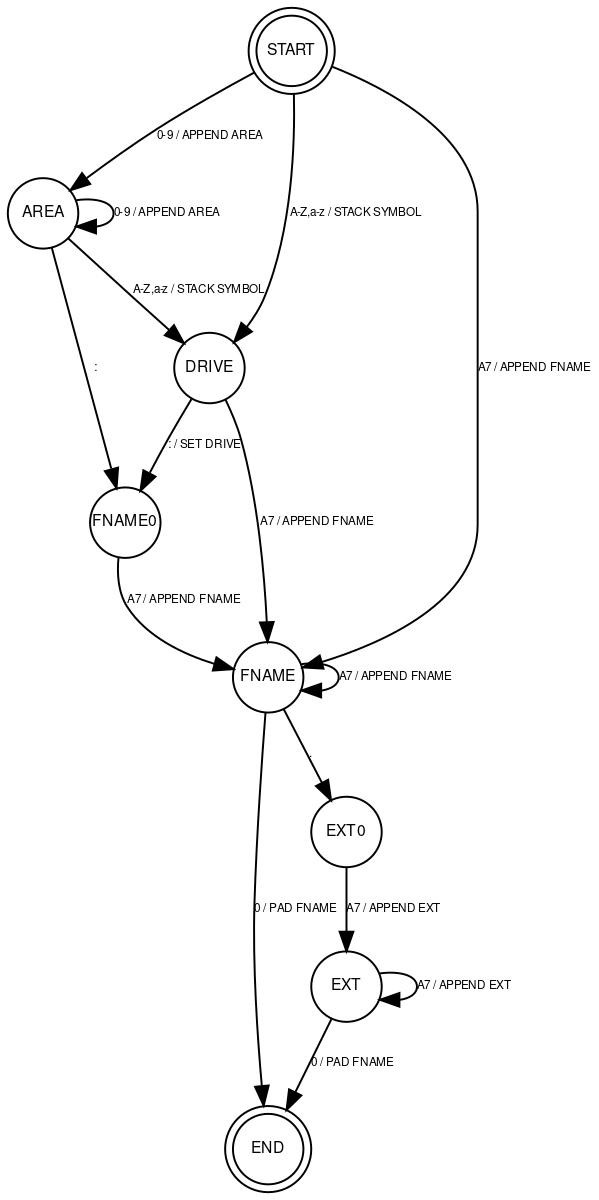

The Complete Finite-State Machine

We got everything figured out. Now it's time to build the real finite-state machine we're gonna use for the task.

Encoding

The machine has eight states and we can represent them using just 3 bits. We got less than eight functions, which'll take up an additional 3 bits. And we got six conditions, which'll need 3 bits too. This means we can fit each transition into 2 bytes, or all 15 state transitions into 30 bytes. Here's the actual FSM definition in Z80 assembly language.

;; automata states

.equ S_START, 0b00000000

.equ S_AREA, 0b00000001

.equ S_DRIVE, 0b00000010

.equ S_FNAME0, 0b00000011

.equ S_FNAME, 0b00000100

.equ S_EXT0, 0b00000101

.equ S_EXT, 0b00000110

.equ S_END, 0b00000111

;; automata test

.equ T_ELSE, 0b00000000

.equ T_DIGIT, 0b00010000

.equ T_COLON, 0b00100000

.equ T_DOT, 0b00110000

.equ T_ALPHA, 0b01000000

.equ T_ASCII7, 0b01010000

.equ T_ZERO, 0b01100000

;; automata functions

.equ F_NONE, 0b00000000

.equ F_APPEND_AREA, 0b00010000

.equ F_STACK_SYM, 0b00100000

.equ F_SET_DRV, 0b00110000

.equ F_APPEND_FNAME, 0b01000000

.equ F_APPEND_EXT, 0b01010000

;; ----- automata definition ------------------------------------------

;; each transition is 2 bytes

;; byte 0:

;; TTTTSSSS T=test, S=start

;; byte 1:

;; FFFFEEEE F=function, E=end

;; example:

;; 00010000, 00000001 (start=0, test=1, function=0, end=1)

fpa_automata:

.db S_START + T_DIGIT, S_AREA + F_APPEND_AREA

.db S_START + T_ALPHA, S_DRIVE + F_STACK_SYM

.db S_START + T_ASCII7, S_FNAME + F_APPEND_FNAME

.db S_AREA + T_DIGIT, S_AREA + F_APPEND_AREA

.db S_AREA + T_COLON, S_FNAME0 + F_NONE

.db S_AREA + T_ASCII7, S_DRIVE + F_STACK_SYM

.db S_DRIVE + T_COLON, S_FNAME0 + F_SET_DRV

.db S_DRIVE + T_ASCII7, S_FNAME + F_APPEND_FNAME

.db S_FNAME0 + T_ASCII7, S_FNAME + F_APPEND_FNAME

.db S_FNAME + T_ASCII7, S_FNAME + F_APPEND_FNAME

.db S_FNAME + T_ZERO, S_END + F_NONE

.db S_FNAME + T_DOT, S_EXT0 + F_NONE

.db S_EXT0 + T_ASCII7, S_EXT + F_APPEND_EXT

.db S_EXT + T_ASCII7, S_EXT + F_APPEND_EXT

.db S_EXT + T_ZERO, S_END + F_NONE

efpa_automata:

The Implementation

Our target is to write following parse function. We will pass it the path and it will parse it and populate our fcb structure and the user area.

extern uint8_t fparse(char *path, fcb_t *fcb, uint8_t *area);

The CP/M fcb_t type is defined as

typedef struct fcb_s {

uint8_t drive; /* 0 -> Searches in default disk drive */

char filename[8]; /* file name ('?' means any char) */

char filetype[3]; /* file type */

uint8_t exn; /* CP/M extent */

uint16_t resv; /* reserved for CP/M */

uint8_t rc; /* records used in extent */

uint8_t alb[16]; /* allocation blocks used */

uint8_t seqreq; /* sequential records to read/write */

uint16_t rrec; /* rand record to read/write */

uint8_t rrecob; /* rand record overflow byte (MS) */

} fcb_t; /* file control block */

We will only populate the first three members of this structure: drive, filename, and filetype. The filename and filetype members must be padded with spaces if shorter than the allocated space.

The SDCC compiler will place function arguments on the stack from last to first. The last value on the stack will be the return address. Here's the code that pops the function arguments up and initializes the fcb_t structure.

_fparse::

;; fetch args from stack

pop af ; ignore the return address...

pop hl ; pointer to path to hl

exx

;; pad filename and extension (of FCB) with spaces

pop de ; pointer to fcb to de

push de ; return it

xor a ; a=0

ld (de),a ; default drive

inc de ; skip over default

ld b,#11 ; 8+3 filename

ld a,#' ' ; pad with spaces

fpa_init_fcb:

ld (de),a

inc de

djnz fpa_init_fcb

pop de ; restore de

pop bc ; pointer to area to bc

exx

;; restore stack and make iy point to it

ld iy,#-8

add iy,sp

ld sp,iy

The arguments for the function will not be needed once they're moved to the registers, so why not put that 8 bytes of space to good use and store some FSM local variables there? This is what the code's gonna keep in that space:

;; we will use space from 2(iy) to 7(iy) as

;; local variables ... overwriting function arguments

ld 2(iy),#S_START ; initial state to 2(iy)!

ld 3(iy),#R_UNEXPECT ; status is unexpected

ld 4(iy),#DEFAULT_AREA ; default area

ld 5(iy),#NO_SYM ; stacked symbol

ld 6(iy),#0 ; fname len

ld 7(iy),#0 ; ext len

Now let's write the main parser routine. Recall that the address of the path is stored in the HL register.

fpa_nextsym:

;; fetch next symbol / character

ld a,(hl)

push hl ; store hl!

;; find the matching transition in the transition table

call fpa_find_transition

;; if not found then unexpected error

jr nz,fpa_done

;; else transition function id is in register l, call it!

call fpa_execfn

jr nz,fpa_done ; if not zero then status!

;; is it final state?

ld a,2(iy)

and #0x0f

cp #S_END

jr z,fpa_done

;; loop

pop hl ; restore hl

inc hl ; next symbol

jr fpa_nextsym ; and loop

This routine's got a simple job, it grabs a symbol (a character) from the filename. Then, using both the symbol and the current state, it calls the fpa_find_transition function to find the right transition. If it can't find it, it throws an error. But if it does, it calls the function and moves on to the next transition. And before grabbing the next symbol, it takes a quick check to see if it's reached the final state.

We locate the transition by looping through the entire finite-state machine and searching for the right one.

;; find transition

fpa_find_transition:

ld hl,#fpa_automata ; address of mealy automata

;; b=total transitions

ld b,#((efpa_automata-fpa_automata)/2)

ld c,a ; store a

fpaft_loop:

ld a,(hl) ; get first byte

and #0b00001111 ; get state

cp 2(iy) ; is it current state?

call z,fpaft_test ; call test

jr nz,fpaft_next ; test failed, next trans.

inc hl ; get next byte

ld a,(hl) ; get second byte to a

and #0b00001111 ; grab next state

ld 2(iy),a ; store to current state

ld a,(hl) ; get second byte to a

and #0b11110000 ; extract function

ld l,a ; get function to l

;; and return success

xor a

ld a,c

ret

fpaft_next:

inc hl ; next state

inc hl

djnz fpaft_loop ; and loop it

;; if we are here, we did not find

;; the transition. clear zero flag!

fpaft_unexpect_sym:

ld 3(iy), #R_UNEXPECT

fpaft_set_z:

xor a

cp #0xff ; rest z flag

ld a,c ; resotre a

ret

The fpaft_test function goes through the conditions specified in the transition and sets the Z flag if everything checks out.

And to wrap things up, the logic for filling in the fcb_t and return arguments is tucked away in the FSM functions. Here's an example of the SET DRIVE function, just to give you an idea.

;; set drive

fpafn_set_drv:

ld a,5(iy) ; get stacked symbol

ld 5(iy),#0 ; empty stack

exx

ld (de),a ; first byte of FCB

exx

xor a

ret

Click here to see the complete source code of the parser finite state machine, described in this article.